I am going to start this post with a confession that my knowledge of the architecture and mechanics of AI are pedestrian and that there will be things that I don’t get right in this post. That said, DeepSeek’s abrupt entry into the AI conversation has the potential to change the AI narrative, and as it does, it may also change the storylines for the many companies that have spent the last two years benefiting from the AI hype. I first

posted about AI in the context of valuing Nvidia, in June 2023, when there was still uncertainty about whether AI had legs. A little over a year later, in September 2024, that question about AI seemed to have been answered in the affirmative, for most investors, and

I posted again after Nvidia had a disappointing earnings report, arguing that it reflected a healthy scaling down of expectations. As talk of AI disrupting jobs and careers also picked up, I also posted a

piece on the threat that AI poses for all of us, with its capacity to do our jobs, at low or no cost, and what I saw as the edges I could use to keep my bot at bay. For those of you who have been tracking the market, the AI segment in the market has held its own since September, but even before the last weekend, there were signs that investors were sobering up on not only how big the payoff to AI would be, but how long they would have to wait to get there.

The AI story, before DeepSeek

The AI story has been building for a while, reflecting the convergence of two forces in technology – more computing power, often in smaller and smaller packages, and the accumulation of data, on technology platforms and elsewhere. That said, the AI story broke out to the public on November 30, 2022, when OpenAI launched ChatGPT, and it made its presence felt in homes, schools and businesses almost instantaneously. It is that wide presence in our daily lives that laid the foundations for the AI story, where evangelists sold us on the notion that AI solutions would make our lives easier and take away the portions of our work that we found most burdensome, and that the businesses that provided these solutions would be worth trillions of dollars.

As the number of potential applications of AI proliferated, thus increasing the market for AI products and services, another part of the story was also being put into play. AI was framed as being made possible by the marriage of incredibly powerful computers and deep troves of data, effectively setting the stage for the winners, losers, and wannabes in the story. The first set of companies were perceived as benefiting from building the AI architecture, with the advance spending on this architecture coming from the companies that hoped to be players in the AI product and service markets:

- Computing Power: In the AI story that was told, the computers that were needed were so powerful that they needed customized chips, more powerful and compact than any made before, and one company (Nvidia), by virtue of its early start and superior chip design capabilities, stood well above the rest. Not only did Nvidia have an 80% market share of the AI chip market, as assessed in 2024, the lead and first-mover advantage that the company possessed would give it a dominant market share, in the much larger AI chip market of the future. Along the way, the the AI story picked up supercomputing companies, as passengers, again on the belief that Ai systems would find a use for them.

- Power: In the AI story, the coupling of powerful computing and immense data happens in data centers that are power hogs, requiring immense amounts of energy to keep going. Not surprisingly, a whole host of power companies have stepped into the breach, with some increasing capacity entirely to service these data centers. Some of them were new entrants (like Constellation Energy), whereas others were more traditional power companies (Siemens Energy) who saw an opening for growth and profitability in the AI space.

- Data: A third beneficiary from the architecture part of the AI story were the cloud businesses, where the big data, collected for the AI systems would get stored. The big tech companies with cloud arms, particularly Microsoft (Azure) and Amazon (AWS) have benefited from that demand, as have other cloud businesses.

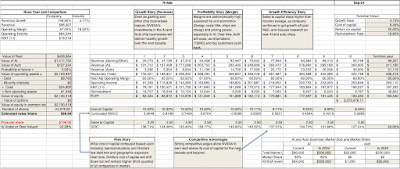

Since the companies involved in building the AI infrastructure are the ones that are most tangibly (and immediately) benefiting from the AI boom, they are also the companies that have seen the biggest boost in market cap, as the AI story heated up. In the graph, I have picked on a subset of high-profile companies that were part of the AI market euphoria and looked at the consequent increase in their market capitalizations:

Using the ChatGPT introduction on November 30, 2022, as the starting point for the AI buzz, in public consciousness and markets, the returns in 2023 and 2024 are a composite (albeit a rough) measure of the benefits that AI has generated for these companies. Note that the biggest percentage winner, at least in this group was Palantir, up 1285% in the last two years, but the biggest winner in absolute terms was Nvidia, which gained almost $ 3 trillion in value in 2023 and 2024.

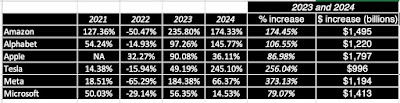

The investments in that AI architecture were being made, with the expectation that companies that invested in the architecture would be able to eventually profit from developing and selling AI products and services. Since the AI storyline required immense upfront investing in computing power and access to big data, the biggest investors in AI architecture were big tech companies, with Microsoft and Meta being the largest customers for Nvidia chips in 2024. In the table below, I look at the Mag Seven, not inclusive of Nvidia, and examine the returns that they have made in 2023 and 2024:

As you can see, the Mag Seven carried the market in the two years, each adding a trillion (or close, in the case of Tesla) dollars in value in the last two years, with some portion of that value attributable to the AI story. With requirements for large investment up front acting as entry barriers, the expectation was these big tech companies would eventually not only be able to develop AI products and services that their customers would want, but charge premium prices (and earn higher margins).

In the picture below, I have tried to capture the essence of AI story, with the potential winners and losers at each stage:

There are parts to this story where there is much to be proved, especially on the AI product and service part, and while investors can be accused of becoming excessively exuberant about the story, it is a plausible one. In fact, my most recent (in September 2024) valuation of Nvidia bought into core elements of the story, though I still found it overvalued:

Note that the big AI story plays out in these inputs in multiple places:

- AI chip market: My September 2024 estimate for the size of the AI chip market was $500 billion, which in turn was justifiable only because the AI product and service market was expected to huge ($3 trillion and beyond).

- Nvidia market share: In my valuation, I assumed that Nvidia’s lead in the AI chip business would give the company a head start, as the business grew, and to the extent that demand is sticky (i.e., once companies start build data centers with Nvidia chips, it would be difficult for them to switch to a competitor), Nvidia would maintain a dominant market share (60%) of the expanded AI chip market.

- Nvidia margins: Nvidia has had immense pricing power, posting nosebleed-level gross and operating margins, while TSMC (its chip maker) has generated only a fraction of the benefits, and its biggest customers (the big tech companies) have been willing to pay premium prices to get a head start in building their AI architecture. Over time, I assumed that Nvidia would see its margins drop, but even with the drop, their target margin (60%) would resemble those of very successful, software companies, not chip making companies.

My concern in September 2024, and in fact for the bulk of the last two years, was not that I had doubts about the core AI story, but that investors were overpaying for the story. That is partly why, I have shed portions of my holdings in Nvidia, selling half my holdings in the summer of 2023 and another quarter in the summer of 2024.

The AI Story, after DeepSeek

I teach valuation, and have done so for close to forty years. One reason I enjoy the class is that you are never quite done with a valuation, because life keeps throwing surprises at you. The first session of my undergraduate valuation class was last Wednesday (January 22), and during the course of the class, I talked about how a good valuation connects narrative to numbers, and followed up by noting that even the most well thought through narratives will change over time. I am not sure how much of that message got through to my studentls, but the message was delivered much more effectively by DeepSeek’s entry into the AI story over the weekend, and the market shakeup that followed when markets opened on Monday (January 27).

A DeepSeek Primer

The DeepSeek story is still being told, and there is much we do not know. For the moment, though, here is what we know. In 2010, Liang Wenfeng, a software engineer, founded DeepSeek as a hedge fund in China, with the intent of using artificial intelligence to make money. Unable to get traction in that endeavor, and facing government hostility on speculative trading, he pivoted in 2023 into AI, putting together a team to create a Chinese competitor to OpenAI. Since the intent was to come up with a product that could be sold at bargain prices, DeepSeek did what disruptors have always done, which is look for an alternate path to the same destination (providing AI products that work). Rather than invest in expensive infrastructure (supercomputers and data centers), DeepSeek used much cheaper, less powerful chips, and instead of using immense amounts of data, created an AI prototype that could work with less data, using rule-based logic to fill in the gap. While there has been chatter about DeepSeek for weeks, it became publicly accessible at the end of last week (ending January 24), and within hours, was drawing rave reviews from people well versed in tech, as it matched beat ChatGPT at many tasks, and even performed better on scientific and math queries.

There are parts of this story that are clearly for public consumption, more side stories than main story,, and it is best to get them out of the way, before looking at the DeepSeek effect.

- Cost of development: The notion that DeepSeek was developed for just a few million dollars is fantasy, and while there may have been a portion of the development that cost little, the total was probably in the hundreds of millions of dollars and required a lot more resources (including perhaps even Nvidia chips) than the developers are letting on. No matter what the true cost of development is finally revealed to be, it will be a fraction of the money spent by the existing players in building their systems.

- Performance tests: The tests of DeepSeek versus OpenAI (or Claude and Gemini) suggests that DeepSeek not only holds it own against the establishment, but even outperforms them on some tasks. That is impressive, but the leap that some are making to concede the entire AI product and service market to DeepSeek is unwarranted. There are clearly aspects of the AI products and service business, where the DeepSeek approach (of using less powerful computing and data) will be good enough, but there will be other aspects of the AI business, where the old paradigm of super computing power and vast data will still hold.

- A Chinese company: The fact that DeepSeek was developed in China throws a political twist into the story that will undoubtedly play a role in how it develops, but the genie is out of the bottle, even if other governments try to stop its adoption. Adding to the noise is the decision by the company to make DeepSeek open-source, effectively allowing others to adapt and build their own versions.

- Fair or foul: Finally, there has been some news on the legal front, where OpenAI has argued that DeepSeek unlawfully used data that was generated by OpenAI in building their offering, and while part of that lawsuit may just be showboating, it is possible that portions of the story are true and that legal consequences will follow.

While we can debate the what’s and why’s in this story, the market reaction this week to the story has been swift and decisive. I graph the performance of the five AI stocks highlighted in the earlier section, throwing in the Meta and Microsoft for good measure, on a daily basis in 2025.

As you can see in this chart, Nvidia Broadcom, Constellation and Vistra have had terrible weeks, losing more than 10% in the last week, but just for perspective, also note that Constellation and Vistra are still up strongly for the year. Meta and Microsoft were unaffected, and so was Palantir, Clearly, the DeepSeek story is playing out differently for different companies in the AI space, but its overall market impact has been substantial, and for the most part, negative.

What is it that makes the DeepSeek story so compelling? First, is the technological aspect of coming up with a product, with far less in resources that the establishment, and I have nothing but admiration for the DeepSeek creators, but the part of the story that stands out is that the they chose not to go with the prevailing narrative (the one where Nvidia chips and huge data bases are a necessity) and instead asked the question of what the end products and services would look like, and whether there was an easier, quicker and cheaper way of getting there. In hindsight, there are probably others who are looking at DeepSeek and wondering why they did not choose the same path, and the answer is that it takes courage to go against the conventional wisdom, especially when, as AI did over the last two years, it sweeps everyone (from tech titans to individual investors) along with its force.

The truth is that even if DeepSeek is stopped through legal or government action or fails to deliver on its promises, what its entry has done to the AI story cannot be undone, since it has broken the prevailing narrative. I would not be surprised if there are a dozen other start-ups, right now, using the DeepSeek playbook to come up with their own lower-cost competitors to prevailing players. Put simply, the AI story’s weakest links have been exposed, and if this were the tale about the Emperor’s new clothes, the AI emperor is, if not naked, is having a wardrobe malfunction, for all to see.

The Story Effect

In this first week, as is to be expected, the response has been anything but reasoned. If you are a voracious reader of financial news (I am not), you have probably seen dozens of “thought pieces” from both technology and market experts claiming to foretell the future, and even among the few that I have read, the views range the spectrum on how DeepSeek changes the AI story.

In my writings on narrative and numbers, where I talk about how every valuation tells a story, I also talk about how stories are dynamic, with a story break representing radical change (where a great story can crash and burn or a small story can break out to become a big one), a story change can be a significant narrative alteration (where a story adds or loses a dimension with big value effects) or a story shift (where the core story remains unchanged, but the parameters can change). Using the pre-DeepSeek story as a starting point, you can classify the narratives on what is coming on the story break/story change/story shift continuum:

|

|

With all the caveats, including the fact that I am an AI novice, with a deeper understanding of potato chips than computer chips, and that it is early in the game, I am going to take a stand on where in this continuum I see the DeepSeek effect falling. I believe that DeepSeek does change the AI story, by creating two pathways to the AI product and service endgame. On one path that will lead to what I will term the “low intensity” AI market, it has opened the door to lower cost alternatives, in terms of investments in computing power and data, and competitors will flock in. That said, there will remain a segment of the AI market, where the old story will prevail, and the path of massive investments in computer chips and data centers leading to premium AI products and services will be the one that has to be taken.

Note that the entry characteristics for the two paths will also determine the profitability and payoffs from their respective AI product and service markets (that will eventually exist). The “low entry cost” pathway is more likely to lead to commoditization, with lots of competitors and low pricing power, whereas the “high entry cost” path with its requirements for large upfront investment and access to data will create a more restrictive market, with higher priced and more profitable AI products and services. This story leaves me with a judgment call to make about the relative sizes of the markets for the two pathways. I am generalizing, but much of what consumers have seen so far as AI offerings fall into the low cost pathway and I would not be surprised, if that remains true for the most part. The DeepSeek entry has now made it more likely that you and I (as consumers) will see more AI products and services offered to us, at low cost or even for free. There is another segment of the AI products and services market, though, with businesses (or governments) as customers, where significant investments made and refinements will lead to AI products and services, with much higher price points. In this market, I would not be surprised to see networking benefits manifest, where the largest players acquire advantages, leading to winner-take-all markets.

In telling this story, I understand that not only am I going to be wrong, perhaps decisively, but also that it could unravel in record time. I make this leap, not out of arrogance or a misplaced desire to change how you think, but because I own a slice of Nvidia (one quarter of the holding that I had two years ago, but still large enough to make a difference in my portfolio), and I cannot value the company without an AI story in place. That said, the feedback loop remains open, and I will listen not only to alternate opinions but also follow real world developments, in the interests of telling a better story.

The Value Effect

Now that my AI story is in the open, I will use it to revisit my valuation of Nvidia, and incorporate my new AI story in that valuation. Even without working through the numbers, it is very difficult to see a scenario where the entry of DeepSeek makes Nvidia a more valuable company, with the biggest change being in the expected size of the AI chip market:

|

In September 2024 (pre DeepSeek) |

In January 2025 (post DeepSeek) |

| AI chip market size in 2035 |

$500 billion |

$300 billion |

| Nvidia’s market share |

60% |

60% |

| Nvidia’s operating margin |

60% |

60% |

| Nvidia’s risk (cost of capital) |

10.52% _> 8.49% |

11.79% -> 8.50% (Higher riskfree rate + higher ERP) |

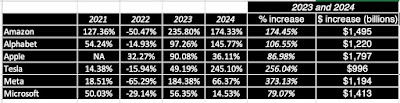

With the changes made, and updating the financials to reflect an additional quarter of data, you can see my Nvidia valuation in the picture below:

There are two (unsurprising) results in this valuation. The value per share that I estimate for Nvidia dropped from $87 in September 2024 to $78 in January 2025, much of that change driven by the smaller AI chip market that comes out of the DeepSeek disruption (with the rest of the decline arising for higher riskfree rates and the equity risk premiums). The other is that the stock is overvalued, at its current price of $123 per share, even after the markdown this week. Since I found Nvidia overvalued in September 2024, when the big AI story was still in place, and Nvidia was trading at $109, $14 lower than todays price, estimating a lower value and comparing to a higher price makes it even more over valued..

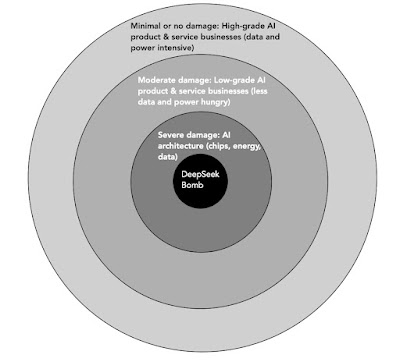

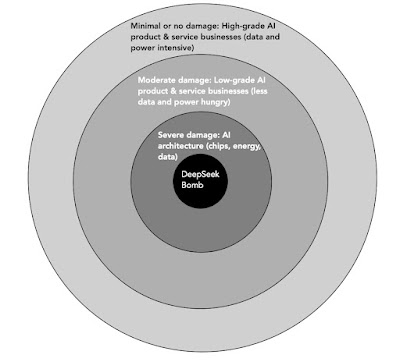

More generally, the value effect of the DeepSeek disruption will be disparate, more negative for some companies in the AI space than others, and perhaps even positive for a few and I have attempted to capture those effects in the picture below, comparing DeepSeek to a bomb, and looking at the damage zones from the blast:

In my view, the damage, in the near and long term, from DeepSeek will be to the businesses that have been the lead players in building the AI architecture. In addition to Nvidia (and its AI chip business), this includes the energy and gas businesses that have benefited from the tens of billions spent on building AI data centers. It is not that they will currently contracts, but that it is likely that you will see a slowing down of commitments to spend money on AI, as companies examine whether they need them. More companies are therefore likely to follow Apple’s path of cautious entry than Meta and Microsoft’s headfirst dive into the AI businesses. As for the businesses that are aiming for the AI products and services market, the effect will depend upon how much these products and services need data and computing power. If the proposed AI products and services are low-grade, i.e., they are more rule-based and mechanical and less dependent on incorporating intuition and human behavior, the effect of DeepSeek will be significant, with lower costs to entry and a commoditized marketplace, with lower margins and intense competition, If on the other hand, the AI products and services are high grade, i.e,, trying to imitate human decision making in the face of uncertainty, the effects of the DeepSeek entry are likely to be minimal and perhaps even non-existent. Thus, I would expect a business that is working on an AI product for financial accounting to find its business landscape changed more than Palantir, working on complex AI products for the defense department or commercial businesses. There is a grouping of companies, primarily big tech firms with large platforms, like Meta and Microsoft, where there may be buyer’s remorse about money already spent on AI (buying Nvidia chips and building data centers) but the DeepSea disruption may make it easier to develop low-cost, low-tech AI products and services that they can offer their platform users (either for free or at low costs) to keep them in their ecosystems.

When faced with a development that could change the way we live and work, it is natural, especially in the early phases, to give that development a catchy name, and use it as a rationale for investing large amounts (if you are a business) or pushing up what you would pay for the businesses in the space (if you are an investor). In my early piece on AI, I talked about four developments in my lifetime that I would classify as revolutionary – personal computers in the 1980s, the internet in the 1990s, the smartphone in the first decade of the twenty first century and social media in the last decade, and how each of these started as catchall buzzwords, before investors and businesses learned to discriminate. Cisco, AOL and Amazon were all born in the internet era, but they had very different business models, and as the internet matured, faced very different end games. I hope that the DeepSeek entry into the AI narrative, and its disparate effects on different businesses in this space, will lead us to be more focused in our AI conversations. Thus, rather than describe a company as an AI company or describe the AI market as “huge”, we should be more explicit about what part of the AI business a company fits into (architecture, software, data or products/services) and apply the same degree of discrimination when talking about AI markets. If you also buy into my reasoning, you may want to follow up by asking whether the AI offering is more likely to fall into the premium or commoditized grouping.

The Bottom Line

My early entry into Nvidia and my holdings of many of the other Mag Seven stocks have allowed me to ride the AI boom, I have remained a skeptic about the product and service side of AI, for much of the last two years. I can attribute that wariness partly to my age, since I cannot think of a single AI offering that has been made to me in the last two years that I would pay a significant additional amount for. I see AI icons on almost everything that I use, from Zoom to Microsoft Word/Powerpoint/Excel to Apple mail. I must admit that they do neat things, including reword emails to not only clean up for mistakes but change the tone, but I can live without those neat add-ons. Since I work in valuation and corporate finance, not a day goes by without someone contacting me about a new AI product or service in the space. Having tried a few out, my response to many of these products and services is that, at least for me, they don’t do enough for me to bother. In many ways, DeepSeek confirms a long-standing suspicion on my part that most AI products and services that we will see, as consumers and even as businesses, fall into the “that’s cute” or “how neat” category, rather than into the “that would change my life”, If that is the case, it has also struck me as overkill to expend tens of billions of dollars building data centers to develop these products, akin to using a sledgehammer to tap a nail into the wall. Every major innovation of the last few decades, has had its reality check, and has emerged the stronger for it, and this may the first of many such reality checks for AI.

I know that much of what I have said here goes against the “happy talk” narrative about AI, emanating from tech titans and business visionaries. I know that Reid Hoffman and Sam Altman believe that AI will be world-changing, in a good way, relieving us of the pain of tasks that are boring and time consuming, and even replacing flawed “human” decisions with be more reasoned AI decisions. They are smart men, but I have two reasons for being cautions. The first is that I have had exposure to smart people in almost every walk of life – smart academics, smart bankers, smart software engineers, smart venture capitalists and yes, even smart regulators – but most of them have had blind spots, perhaps because they hang out with people who think like them. The second, and this perhaps follows from the first, is that I am old enough to have heard this evangelist pitch for a revolutionary change before. In the 1980s, I remember being told that personal computers would eliminate the drudgery of working through ledger sheets with calculators and pencils, but as young financial analysts will tell you today, it has just created a fresh and perhaps even more soul-sucking drudgery, where monstrously large spreadsheets govern their workdays. In the 1990s, the advocates for the internet painted a picture of the world where access to online information would make us all more informed and wiser, but in hindsight, all it has done is weaken our reasoning muscles (by letting us look up answers online) and made us misinformed. In this century, social media too was born on the promise that it would keep us connected with friends, even if they were thousands of miles away, and happier, because of those connections, but as my good friend, Jonathan Haidt, and others have chronicled, it has left many in its orbit more isolated and less happy than before.

YouTube Video

Nvidia Valuations